Capital Marketing: To Swap Or Not To Swap- That Is The Question | June 2022 Special Report

Rising Interest Rates Place Spotlight on Interest Rate Swaps and Caps; Catapulting Forward Curves Complicate Process

Tightening monetary policy highlights utility of rate swaps and caps.

Commercial real estate investors have long had multiple avenues for hedging against rising interest rates. The Federal Reserve's commitment to raising interest rates, renewed by higher-than-anticipated CPI inflation in May, has brought these options back to the forefront of many borrowers' minds. For investors with floating rate debt, there are two prominent options to hedge against rate climbs: an interest rate swap and cap. A swap offers an investor an opportunity to exchange a floating interest payment for a fixed-rate payment for a certain period of time. A cap, on the other hand, fixes an upper limit on the rate a borrower will pay at the cost of an upfront payment. In the event that interest rates advance higher than the market anticipated, these types of positions can help investors avoid additional capital costs. However, if rates do not rise as much as expected, the borrower may have spent capital unnecessarily or incurred additional cost.

Betting on the SOFR forward curve.

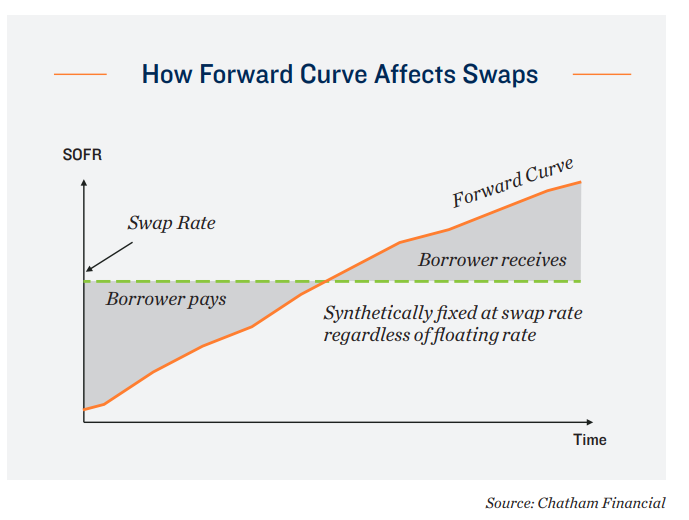

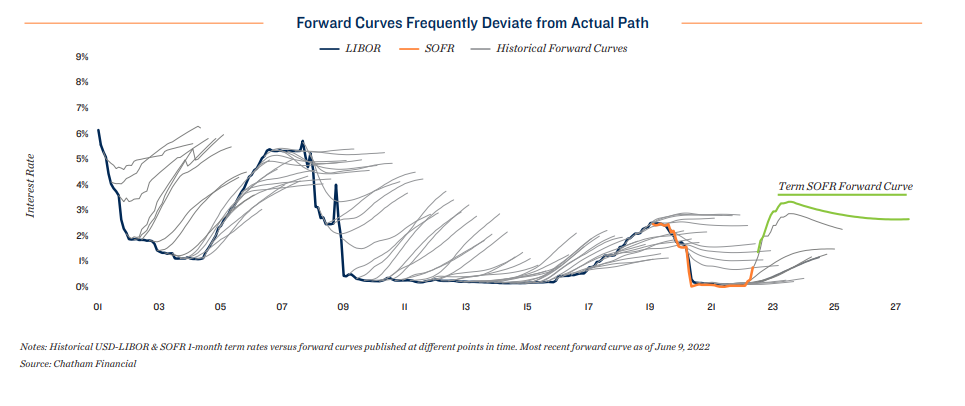

Swaps and caps pricing is based on, among other things, the forward curves, which is the market's expectation for where that index will go in the future. As such, changes to the forward curve can dramatically impact the pricing for both new and existing derivatives. The commonly used benchmark is the SOFR forward curve, which in the last year has changed from a relatively flat horizontal line to a steep, almost vertical, line in the coming years. The SOFR forward curve is the future expectation of how the SOFR base rate will change over time, and is somewhat of a "betting line" of where it will settle in the coming months and years. The forward curve is a dynamically moving expectation and can shift greatly due to market forces. That said, it is a projection, and history shows us that it tends to be more wrong than it is right at any given time.

Use of forward curves to hedge.

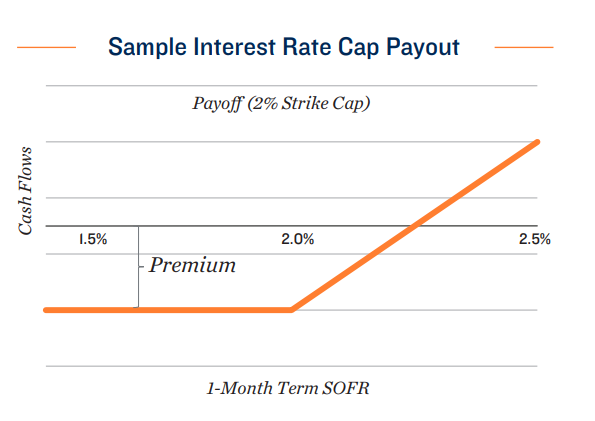

When a borrower utilizes a swap or a cap, they are hedging their interest rate based on this forward curve. By executing a swap, the floating rate loan from a bank synthetically becomes fixed, at more or less the average interest rate of the forward curve at that time over the swap term. If the borrower were to prepay their loan sometime in the future, the unwind could be an asset or a liability, depending on where the swap rate is at that time for the remaining term. It is important to consider prepayment risk when entering into a swap, although it is worth noting that the prepayment will always be less than yield maintenance or a defeasance because it is an index to index comparison and you do not need to prepay on the spread component. When a borrower utilizes an interest rate cap, they pay an upfront cost to cap the base rate at a fixed "strike price" for a certain period. This is akin to insurance against paying a higher rate, but the borrower is still taking the risk that the price they pay up front is worth the savings the borrower will receive during the term of the loan while the cap is in place.

Key Terms to Know

• Interest Rate Swap: Ability for a borrower to exchange a loan with a floating interest rate for a fixed rate profile for a certain length of time. The fixed rate is based on the current forward curve for the benchmark interest rate. A common benchmark rate used today is SOFR.

• SOFR: The Secured Overnight Financing Rate is a broad measure of the cost of borrowing cash overnight, collateralized by Treasury securities. The SOFR is calculated as a volume-weighted median of transaction level data from the Bank of New York Mellon and the U.S. Department of the Treasury's Office of Financial Research. A SOFR value is published each business day and is now being used as a replacement benchmark for the sunsetting LIBOR metric.

• Forward curve: A forward curve is the present-day expectation of how a measure will perform in the future. As such, forward curves are dynamic and can shift greatly as perceptions of the future change. Forward curves for benchmark interest rates, such as SOFR, are used for a variety of purposes, including in determining the contractual rate in an interest rate swap and a factor in the price of interest rate caps.

• Two-way Breakage: Transfer of funds when the swap position is terminated. If the contractual rate is less than the market replacement rate, then the borrower receives a payment. The borrower is obligated to pay, however, if the market rate is above the contractual rate.

• Interest Rate Cap: The borrower can set a limit, or strike price, on how high the floating rate goes in their loan by making an up-front payment. The lower the cap (strike) and the longer the term, the greater the up-front cost. The interest rate cap can never be a liability to the purchaser of an interest rate cap, so the total possible cost is the premium paid at the onset. During the term of the cap, the borrower still pays the floating rate as long as it is below the strike price. Caps are a common requirement in bridge lending.

Understanding Swaps in Today's Environment

Interest rate swaps provide more options for borrowers.

Unlike a straight fixed rate loan issued by some financial institutions, a swap is a borrower's choice to take a floating rate, generally more freely pre-payable loan, and make it a fixed rate loan for a certain term. Typically, these terms span five, seven or 10 years. Only banks can be a counterparty in a swap transaction, so in most cases borrowers receiving debt funds or private money loans will not be able to swap their floating interest rate. Banks will increase the swap rate they offer above the fair value swap rate to account for credit risk and to add a profit margin. Unlike straight fixed rate loans, which are only utilized on stabilized properties, a swap could be utilized on a bridge loan or even construction financing, as long as a bank is the lender.

How rates perform against forward curves key to rate swap success.

A risk a borrower takes on a swap is the two-way breakage. This only comes into play when the borrower does not ride out the full term of the swap and prepays their loan at a date prior to maturity. In a rising interest rate environment, the swap can be an asset to the borrower if they were to pre-pay, but in a falling interest rate environment, the swap could be a liability resulting in a hefty prepay penalty to the borrower. After the Great Recession, borrowers had a hard time prepaying their existing loans in 2010-2013 for just this reason. Rates had fallen so dramatically that loans that were swapped in 2004 to 2007 would have resulted in a massive breakage cost to their borrowers. The risk a borrower takes is also more complicated than deciding if rates are increasing or falling in the near term. Ultimately, the swap breakage is the difference between the SOFR forward curve on the day the borrower placed the hedge, versus the actual rate for the remaining term the day the borrower prepays. In other words, the SOFR curve at the time of prepayment determines a swap rate for the remainder of the term, and that is compared against the swap rate that is in place on the loan that is prepaid. If the rate is higher going forward than what is in place, the swap is an asset and the borrower would profit. If the rate is lower going forward than what is in place, the swap is a liability and the borrower would be subject to swap breakage prepayment penalties.

Past cycles offer insights into current swap breakage outcomes.

Past periods of rapidly increasing interest rates may offer some insight into how rates will compare to their forward curves in the coming years. The chart below shows the past 20 years of data with respect to forward curve expectations at various periods overlaid with the actual curve. The data generally shows that in times of rapidly increasing interest rates, the forward curve has generally undershot the actual rate increases. While there is no guarantee this will still be the case in the current environment, with persistently elevated inflation steepening the forward curve and lifting the SOFR projection above 4 percent, there is nevertheless a clear historical trend. Therefore, a swap today would be "in the money" on swap breakage. That said, a swap today results in a very high interest rate to the borrower. A five-year term loan with an interest rate of 225 basis points over the one-month term SOFR rate would still translate to an all-in swapped rate of around 6.00 percent as of June 14. The all-in floating rate as of the same date is only 3.58 percent.

Preparing for the Cost of Today's Interest Rate Caps

Interest rate caps are a common requirement from some lenders.

Borrowing from a debt fund or other floating rate bridge or construction lender often requires purchasing interest rate caps. Depending on the term and the strike price, or the rate at which the SOFR is capped, the price can vary greatly. The lower the strike price and the longer the term, the more the rate cap will cost. While it affords the borrower greater protection, the upfront cost needs to be capitalized through debt and/or equity, and may impact returns or the ability to transact.

Steep forward curve slingshots cap costs.

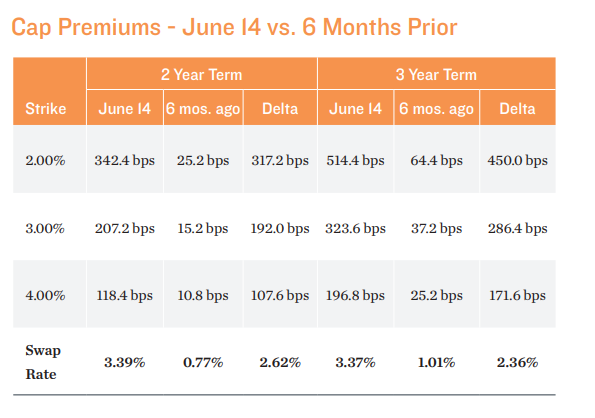

As a hedging instrument, one factor in interest rate caps is the shape of the SOFR forward curve. With the steeply rising forward curve of today, cap costs have skyrocketed. The chart to the right shows the cost of a 2.0 percent, 3.0 percent or 4.0 percent strike price SOFR cap six months ago versus the cap cost as of June 10. The cap cost has increased dramatically, due to the SOFR curve movement. This has resulted in surprises for borrowers who sign a loan application and go into due diligence, only to find that their budget has increased hundreds of thousands, or millions, of dollars due to the interest rate cap cost. Properly budgeting for a rate cap is essential in today's market. Borrowers may also be able to work with the lender to reduce the term or increase the strike price, which could significantly reduce the cost. While the cap will likely have to be extended later, it is possible that the forward curve will have flattened or will be showing a decline by then, thus reducing the cap cost for future years versus what a borrower would have to pay today. Although it is possible, the all-in cost could be great if interest rates rise more than expected.

Exchanging for fixed rates bears significant consideration.

Rate swaps and caps are part of the ordinary course of business in real estate borrowing. While many borrowers have given little thought to them over the past decade due to a low interest rate and low-cost environment, today's forward curve makes it essential that borrowers understand these hedging instruments and the risks and costs associated with them.